One main business for psychologists is to examine questionnaire data. Extraversion, intelligence, attitudes… That’s bread-and-butter job for (research) psychologists.

Similarly, it is common to take the metric level of questionnaire data for granted. Well, not for the item level, it is said. But for the aggregated level, oh yes, that’s OK.

Despite its popularity, the measurement basics of such practice are less clear. On which grounds can this comfortable practice be defended?

In psychology, the classical text book surely is Lord and Novick’s text book (1968) on classical test theory. There, the authors hold some quite lax view on the quantitative attribute of psychological data. Basically, they appear to follow S. S. Stephens theory, that everything can be measured. Stephen’s theory is surely the most liberal definition of measurement (and maybe counter-intuitive for most people). However, his idea makes sense viewed from the broad idea of mapping some empirical domain to a numerical one. The question remaining open is of course: Do the relations of the empirical domain hold in the numerical domain? This is no automatism (probably because in the measurement of length the relations do hold, we assume that they will always hold, which is mistaken).

In measurement theory (particularly for psychology), a authoritative text book is the Foundations of Measurement by Krantz, Luce, Suppes, Tversky. While a definitive resource, it may be more of a resource than one would be happy with for a smooth couch evening :-)

I found this book of Joel Michell to be enlightening; Michell’s criticism on the current practice of measurement is the most pronounced, summarized eg in this paper with the punchy title Normal Science, Pathological Science and Psychometrics. There, Michell argues against the resistance of taking the question of scale level as an empirical one. Surprisingly, psychologists paid little attention and interest to the empirical investigation whether a certain variable possesses metric level; a fact Michell calls a neglect and even a pathology.

One reason of this posited neglect is that methodology is assumed to be missing, that there are no tools for checking whether (or not) a certain variable is metric. However, this view is not quite correct. Psychologist Duncan Luce and statistician John Tukey proposed a theory (conjoint measurement) which can be used for investigating whether a variable is quantitative or not (see 1964 paper).

It is beyond the scope of this article to describe this theory; rather, I would like to demonstrate that metric level cannot be taken for granted. Again, example and intuition based!

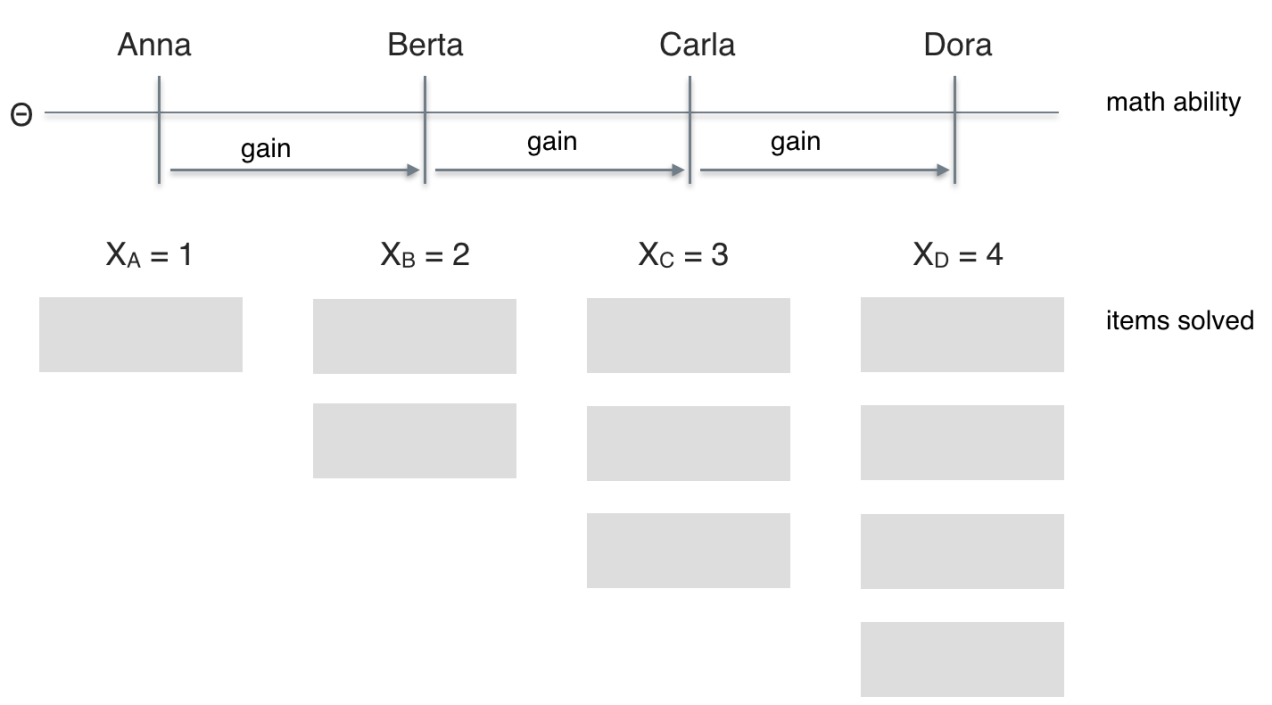

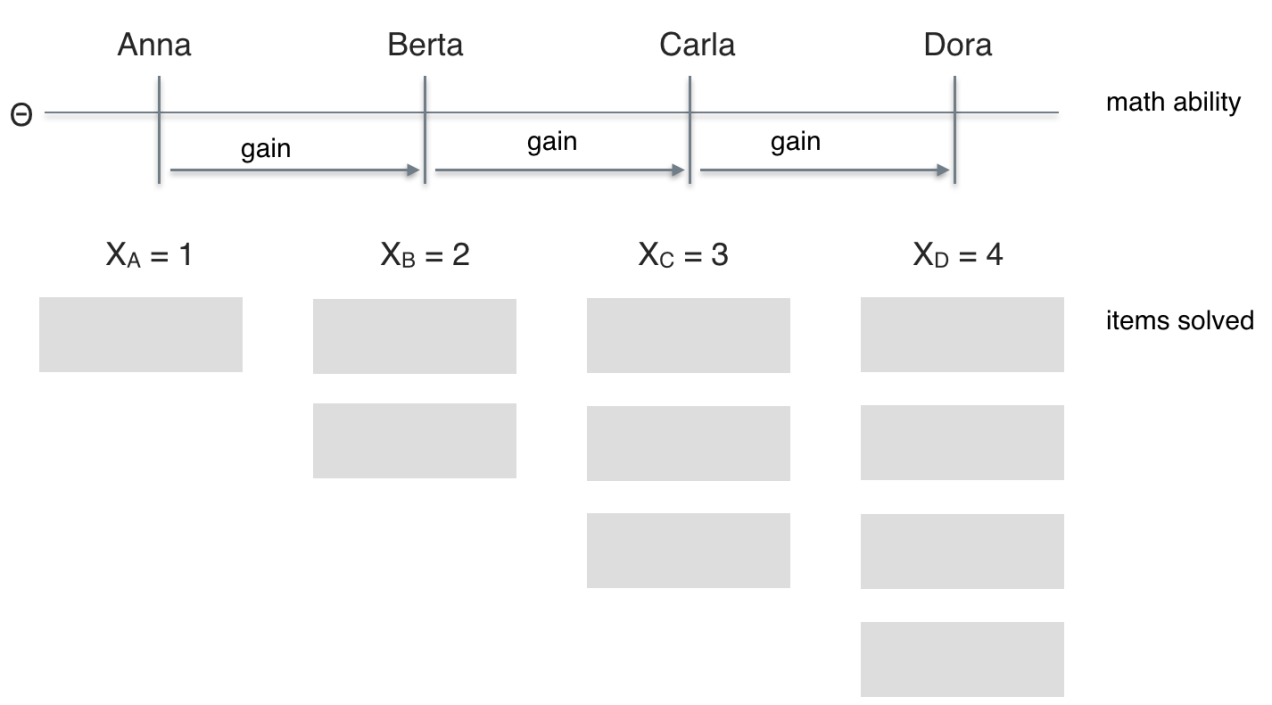

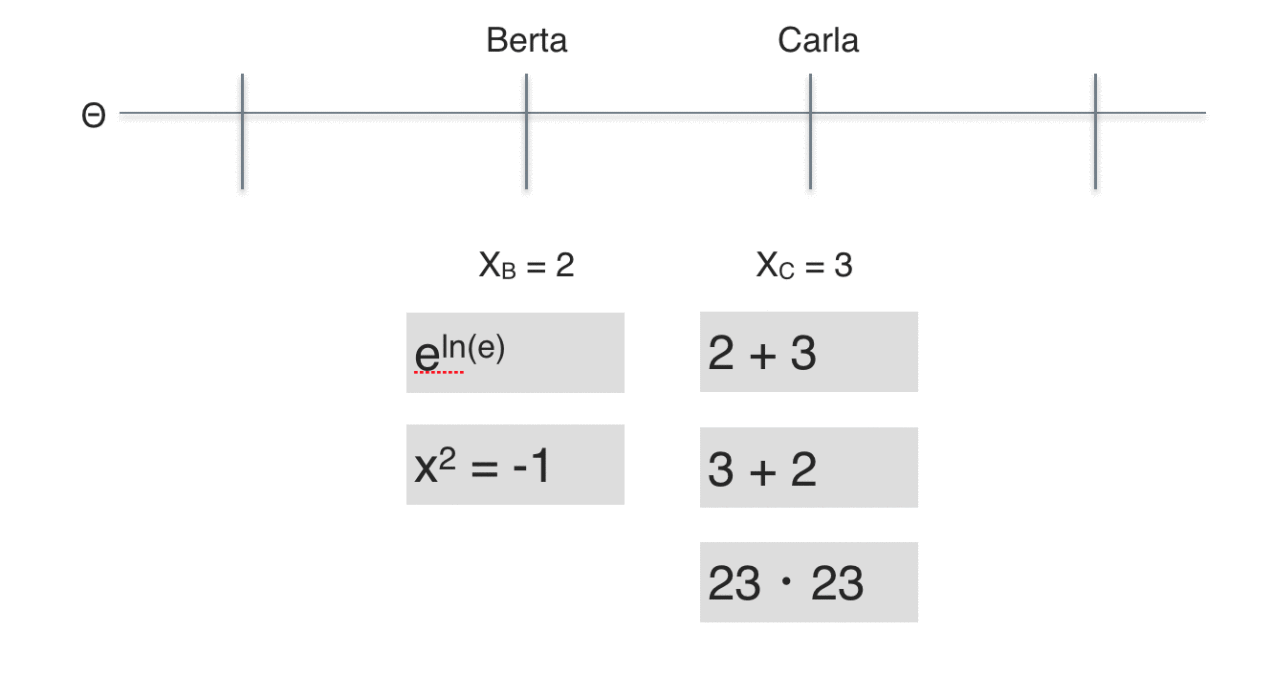

Imagine four students (Anna, Berta, Carla, Dora) probing some math test. Anna solves one item; Berta two; Carla three; Dora four. Thus, the math scores (X) range from 1 (Anna) to 4 (Dora). Let’s assume that higher scores (performance) implies higher math ability (latent psychometric variable, $\theta$. So, the order of ability would be Anna < Berta < Carla < Dora, or, Dora > Carla > Berta > Anna, respectively. Solving one more item translates down to a “gain” in the individual value of the latent variable. In a nutshell, we have established (or assumed) ordinal niveau.

So, let’s look at metric level next. Let’s stick to interval level; ratio level appears out of question for many a psychological variable.

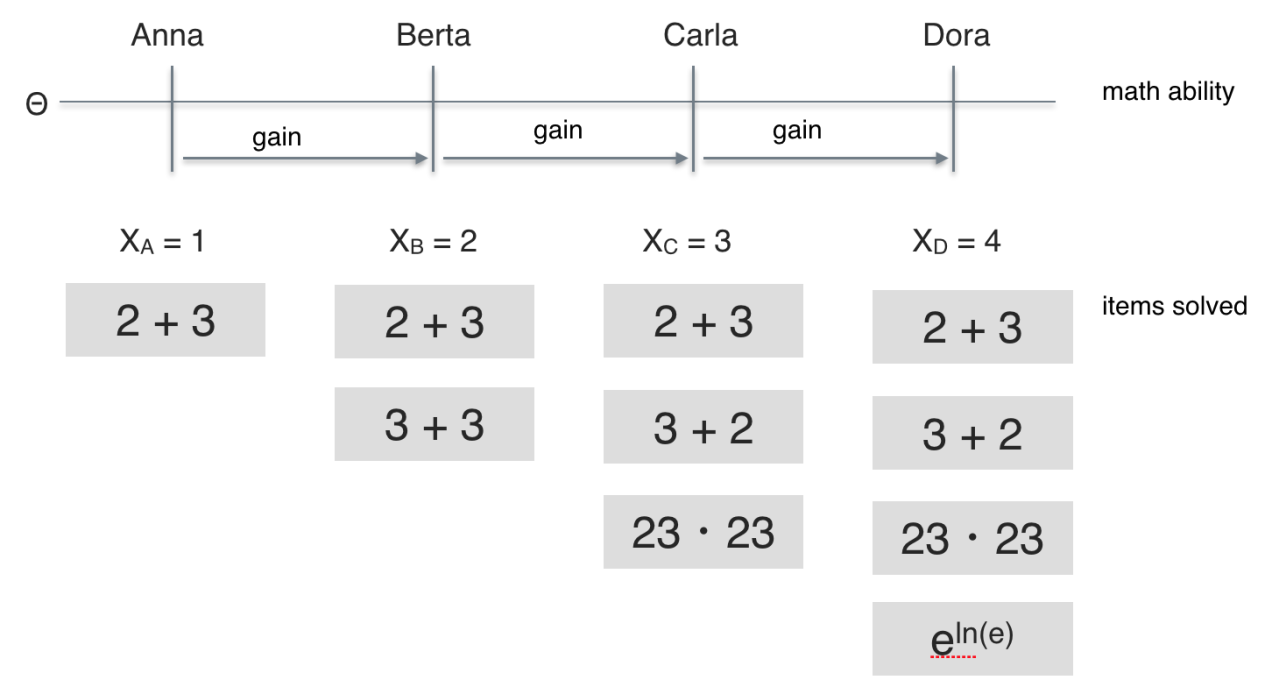

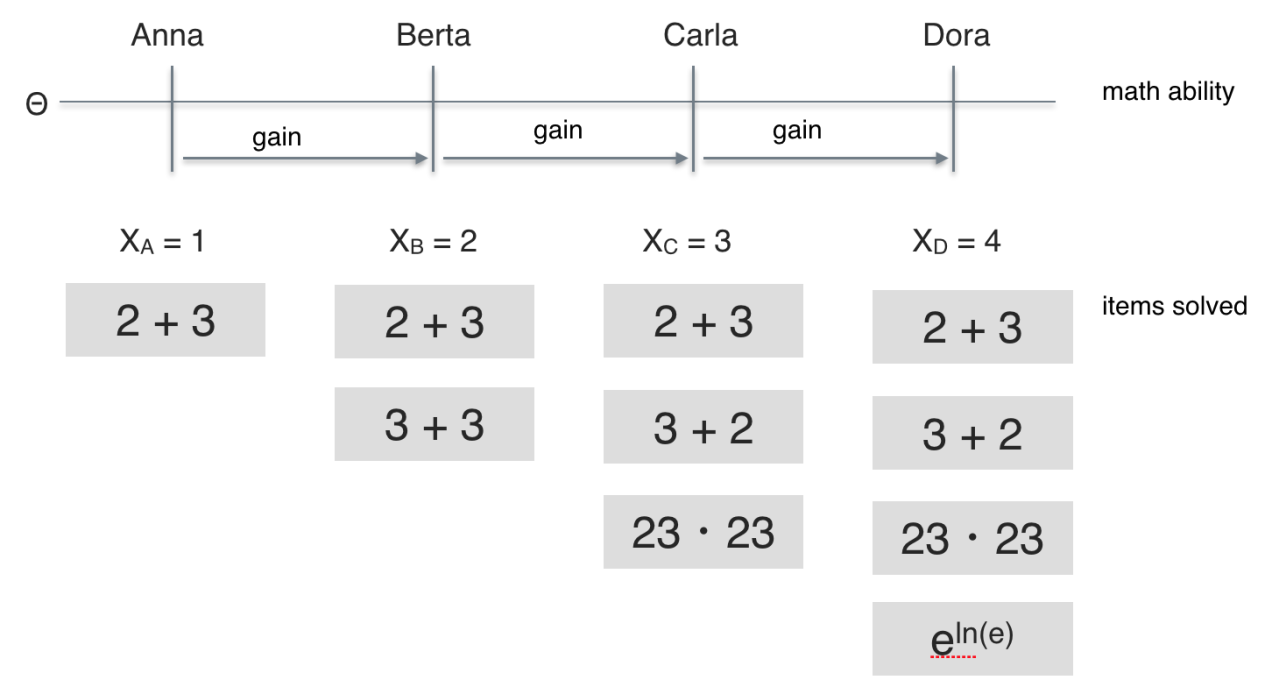

If we look more closely to the items solved we see that they appear to be of different difficulty. Some easier (2+3), some of intermediate difficulty (23*23), and some demanding more advanced knowledge ($e^{lne}$).

So, Berta solved two of the easy items, one easy more item than Anna. But Carla solved a a more difficult item compared to those which were solved by Berta. Thus, the additional ability needed for solving those three items (“gain” in ability) appears greater than the additional ability needed for solving two easy items instead of one. It appears plausible that the ability difference between Anna and Berta is smaller than the ability difference between Berta and Carla. The same reasoning applies for the difference between Carla and Dora.

In sum, equidistance of ability gains appears questionable, at least in this example. More generally, we cannot readily assume equidistance of difficulty/ability differences between adjacent levels. In other words: There are no grounds for assuming metric level just because we have a sum score.

One may argue that the differences could be more or less equal, so that the error should not be too grave. I think a sensible answer would be to test this assertion, and not take it for granted. Given the pivotal of measurement for any empirical science, we should take great care. As a side note, it has been reported that advance in physical science was accompagnied by advance in measurement technology. This alarms us of the importance of measurement theory and practice.

Just as there are optimistic voices about measurement in psychology (“hey no worries, it just works, no need to check”) there are pessimistic voices as well (“there is no quantitative measurement in psychology, just not possible”), see e.g. Guenter Trendler. For example, one could ask whether psychometric variables possess nominal or ordinal level. Consider this example:

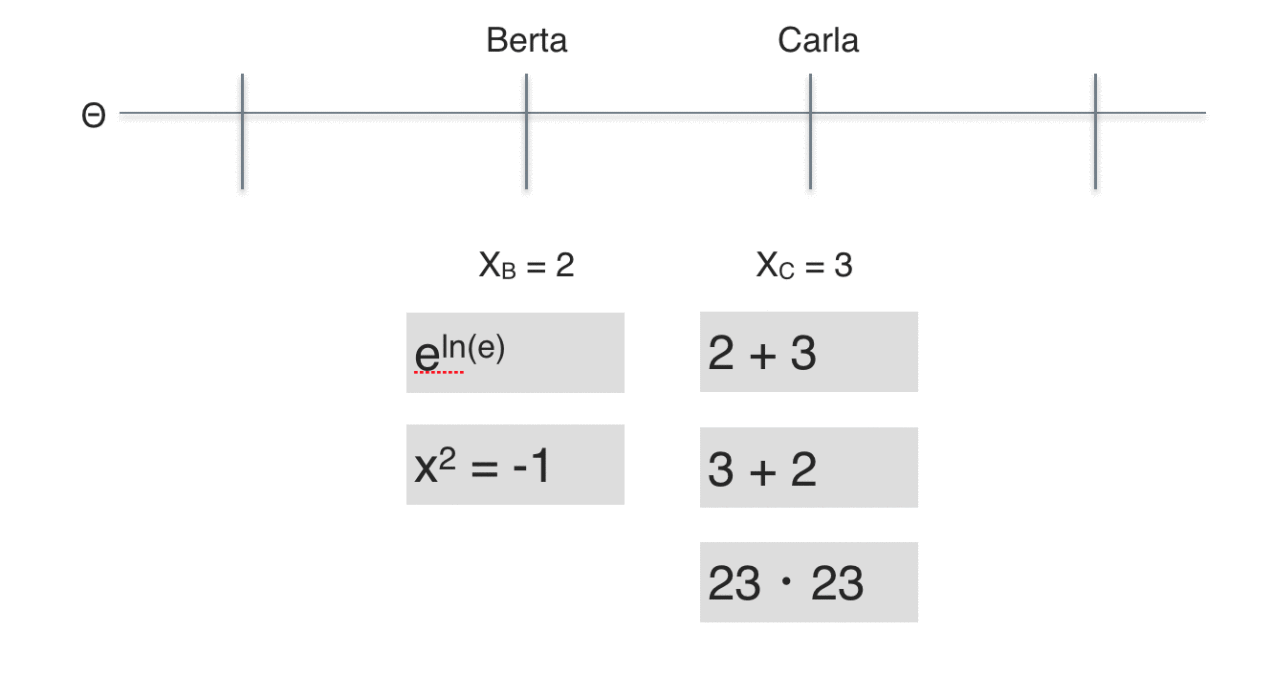

Carla has solved three items ($X_B = 3$) whereas Berta has only solved two ($X_A=2$); one less than Carla. Following the reasoning above, we conclude that Carla exhibits a higher ability compared to Berta.

Looking at the contents of the items, one may doubt whether the ability exhibited by Carla really is greater than Berta’s, because Berta solved more difficult items than Carla did.

Of course there are a number of different aspects that warrant attention, such as whether the items can be seen as of “one type””, so that they are “allowed”” to be summed up. Or whether the Rasch model solves the problem, and guaranties for metric level (it does not).

In sum, the message is that we cannot take metric level for granted. We need to empirically investigate. If we do take metric level for granted, we are prone to a bias of unknown size.