Measuring personality traits is one of (the?) bread-and-butter business of psychologists, at least for quantitatively oriented ones. Literally, thousand of psychometric questionnaires exits. Measures abound. Extroversion, part of the Big Five personality theory approach, is one of the most widely used, and extensively scrutinized questionnaire tapping into human personality.

One rather new, but quite often used questionnaire, is Satow’s (2012) B5T. The reason for the popularity of this instrument is that it runs under a CC-licence - in contrast to the old ducks, which coute chere. The B5T has undergone some psychometric scrutiny, and a number of results support the notion that it is a valid instrument.

Let’s look here into some aspects of validity of the instrument. More bluntly: Does the B5t (here: only extraversion) really measures extraversion? My point is rather not a judgement on this particular instrument, but more which checks can guide us to answer this question.

First, we do not know whether extraversion per se is of metric niveau; can the mind distinguish between infinitely many distinct yet equidistant steps on a imagined continuum? Surely this is a strong assumption. But let’s put that aside for now (as nearly everybody does not only for a moment but forever).

External validity first

A primary check should be the external validity of the scale. When I say external validity, I mean e.g., whether the instrument is correlated with some variable it should be correlated with according to the theory we hold. That is to say, if some “obvious” fact is not identified by a measurement device, we would and should be unwilling to accept whether it really measures what it ought measure.

Note that reliability is not more than a premise or prerequisite for (external) validity. Thus, if we knew some measure is reliable (by standard procedures), we do not know whether it measures what it should measure. To the contrary, if there is some sound association with the right external measure, we are more confident (though maybe not satisfied).

Data & packages

Let’s have a look at our extraversion (e) data. Here we go:

e <- read.csv("https://osf.io/meyhp/?action=download")

The DOI of this data is 10.17605/OSF.IO/4KGZH

We will need these packages:

library(tidyverse)

## Loading tidyverse: ggplot2

## Loading tidyverse: tibble

## Loading tidyverse: tidyr

## Loading tidyverse: readr

## Loading tidyverse: purrr

## Loading tidyverse: dplyr

## Conflicts with tidy packages ----------------------------------------------

## filter(): dplyr, stats

## lag(): dplyr, stats

library(htmlTable)

library(corrr)

library(psych)

##

## Attaching package: 'psych'

## The following objects are masked from 'package:ggplot2':

##

## %+%, alpha

library(plotluck)

Note that recoding has already taken place, and a mean value has been computed; see here for details. The extraversion scale consists of 10 items, which 4 answer categories each. A codebook can be found here: https://osf.io/4kgzh/.

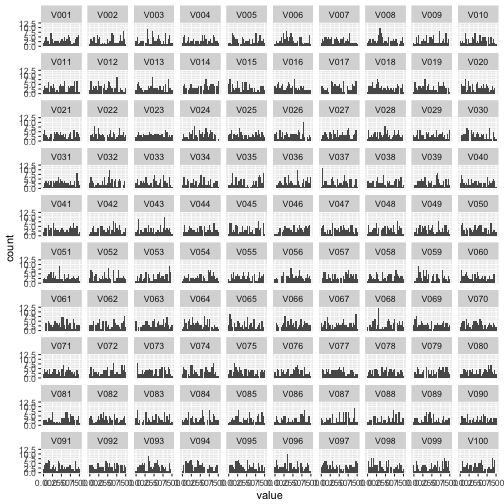

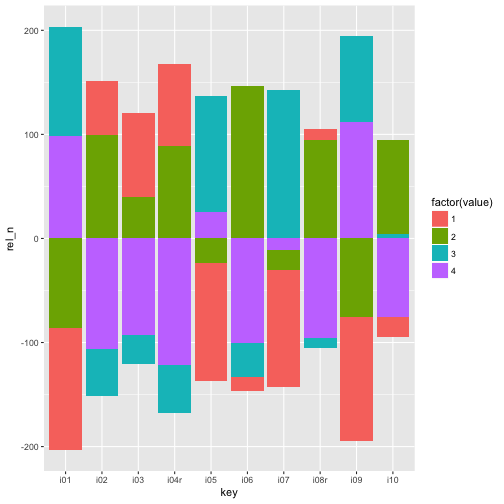

Plotting means and frequencies

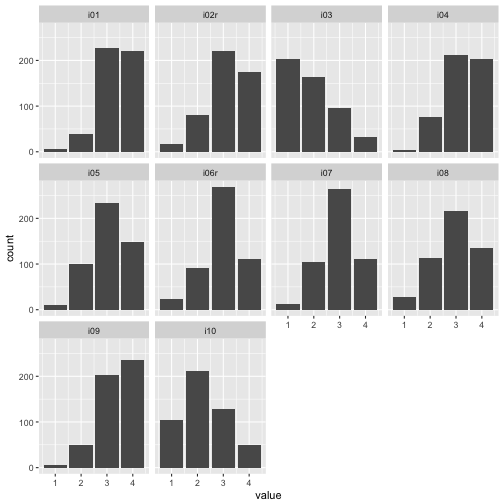

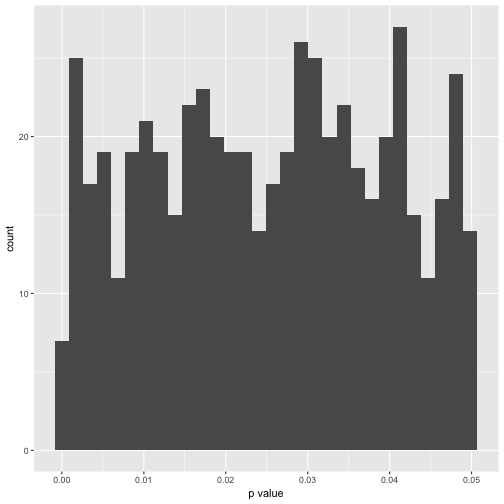

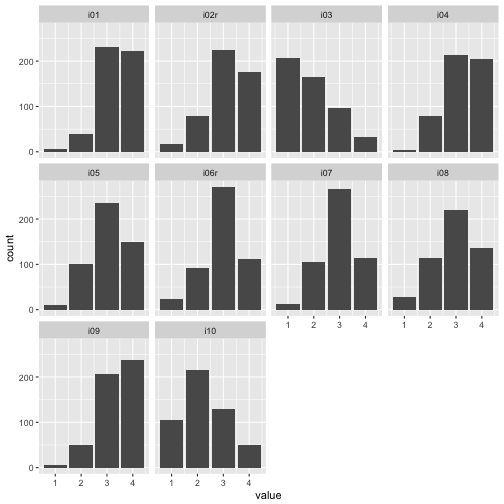

Let’s have a brief look at some stats as first step. Here are the histograms:

e %>%

select(i01:i10) %>%

gather %>%

ggplot +

aes(x = value) +

geom_bar()+

facet_wrap(~key, ncol = 4)

## Warning: Removed 24 rows containing non-finite values (stat_count).

Let’s save this dataframe because we will use it frequently:

e %>%

select(i01:i10) %>%

gather(key = item, value = value) -> e2

And means and SD:

e %>%

select(i01:i10) %>%

gather(key = item, value = value) %>%

group_by(item) %>%

summarise(item_mean = round(mean(value, na.rm = T), 2),

item_sd = round(sd(value, na.rm = T), 2)) -> e_summaries

htmlTable(e_summaries)

| item | item_mean | item_sd | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | i01 | 3.34 | 0.68 |

| 2 | i02r | 3.12 | 0.8 |

| 3 | i03 | 1.91 | 0.92 |

| 4 | i04 | 3.24 | 0.73 |

| 5 | i05 | 3.05 | 0.77 |

| 6 | i06r | 2.94 | 0.77 |

| 7 | i07 | 2.97 | 0.73 |

| 8 | i08 | 2.93 | 0.86 |

| 9 | i09 | 3.35 | 0.71 |

| 10 | i10 | 2.24 | 0.9 |

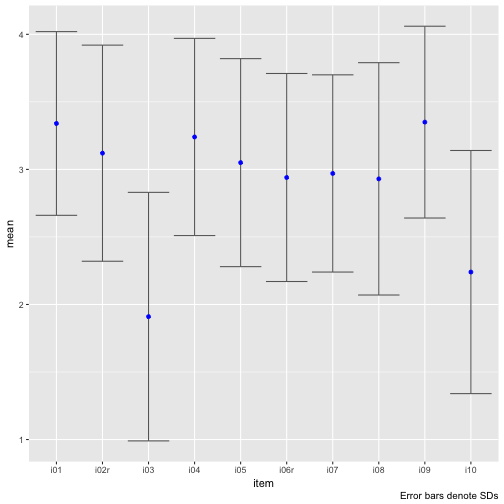

Maybe let’s plot that.

e_summaries %>%

mutate(mean = item_mean,

lower = mean - item_sd,

upper = mean + item_sd) %>%

select(-item_mean) -> e_summaries

e_summaries %>%

ggplot(aes(x = item, y = mean)) +

geom_errorbar(aes(ymin = lower,

ymax = upper),

color = "grey40") +

geom_point(color = "blue") +

labs(caption = "Error bars denote SDs")

Note that scale_y_continuous(limits = c(1,4)) will not work, because this method kicks out all values beyond those limits, which will screw up your error bars (I ran into that problem and it took me a while to see it).

Hm, there appear to types of items, one with a rather large mean, and one with a small mean. The SD appears to bear roughly equal.

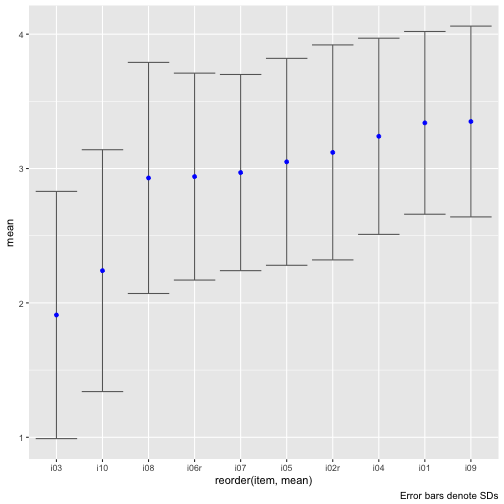

Let’ sort the plot by the item means.

e_summaries %>%

ggplot(aes(x = reorder(item, mean), y = mean)) +

geom_errorbar(aes(ymin = lower,

ymax = upper),

color = "grey40") +

geom_point(color = "blue") +

labs(caption = "Error bars denote SDs")

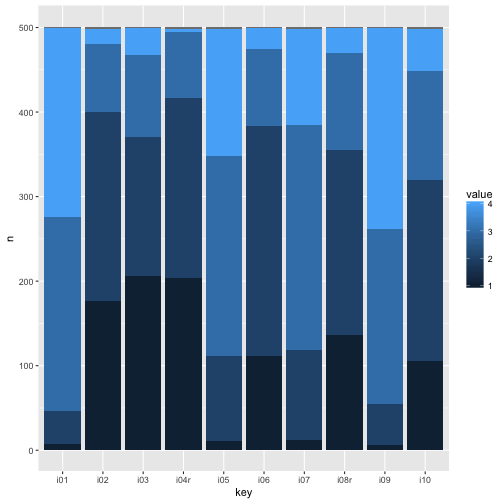

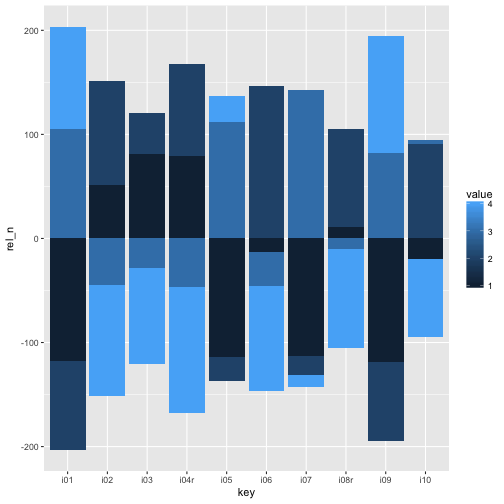

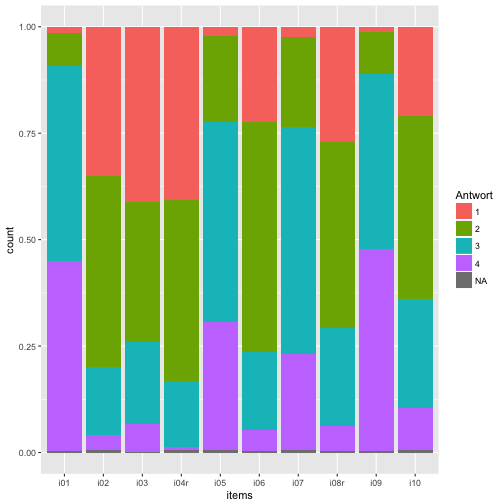

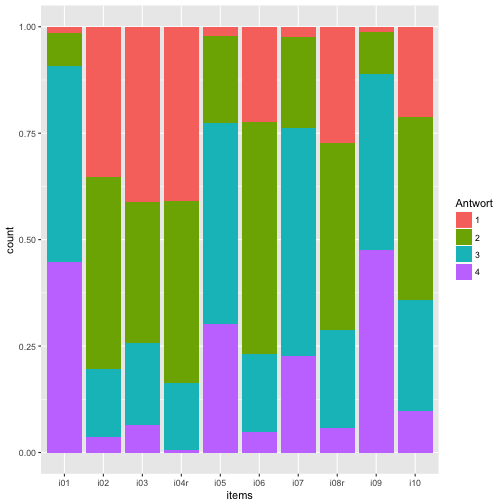

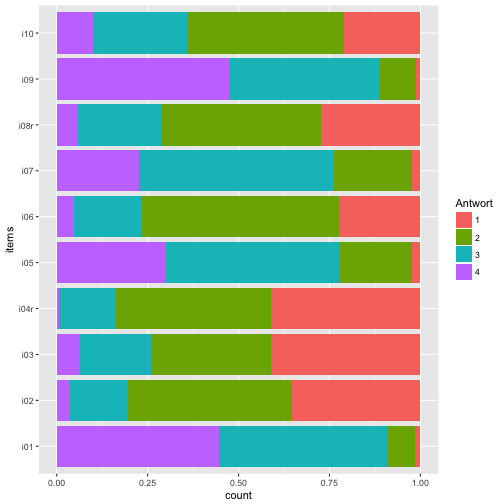

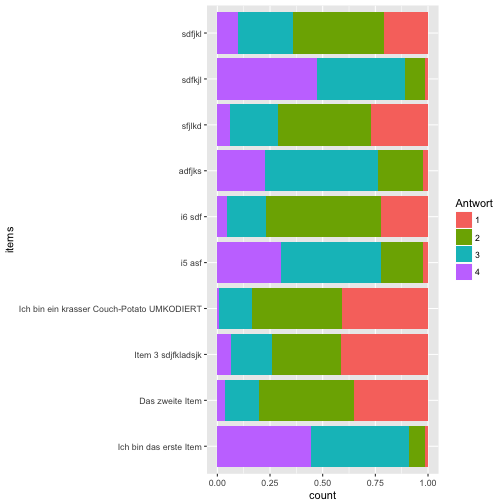

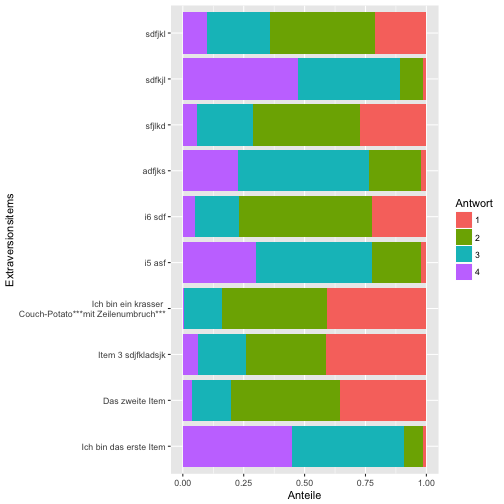

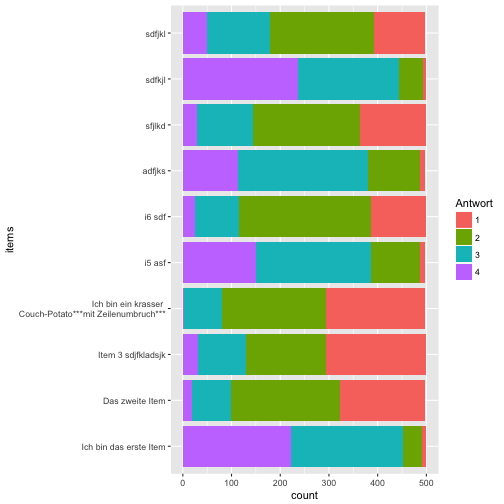

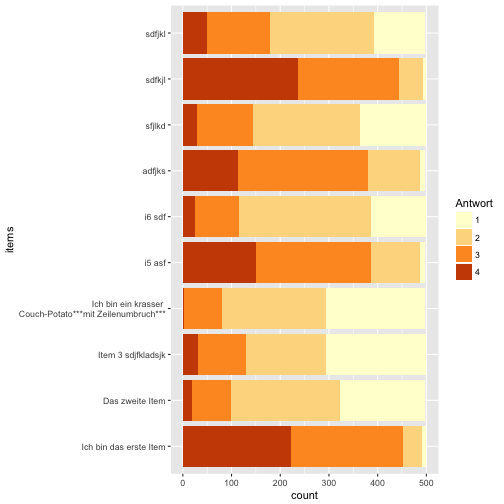

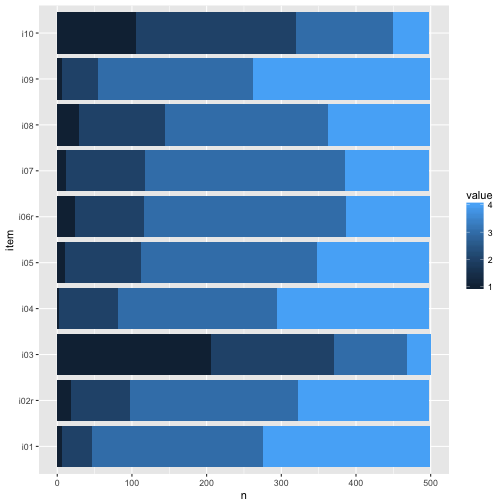

Maybe plot stacked bar plots.

e2 %>%

na.omit %>%

count(item, value) %>%

ggplot +

aes(x = item, y = n, fill = value) +

geom_col() +

coord_flip()

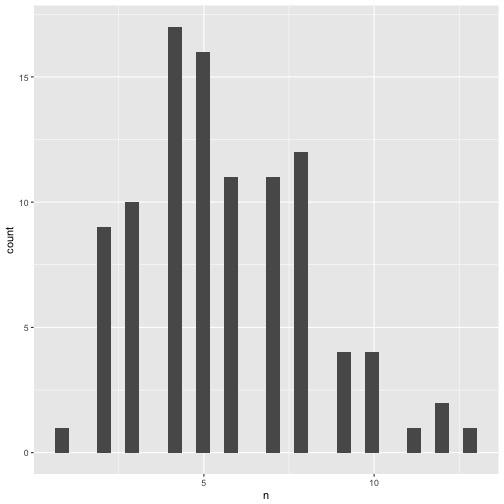

We see that at least the difficulty of the items ranged quite a bit. This last plot surely gives us the best impression on what’s going on. Note that real values have been depicted, not functions of them such as mean or sd.

For example, for nearly all items, mainly categories 3 and 4 were picked. So items were comparatively easy, which is not seldom. Maybe a finer grunalirity at the “bottom” would be of help to get more information.

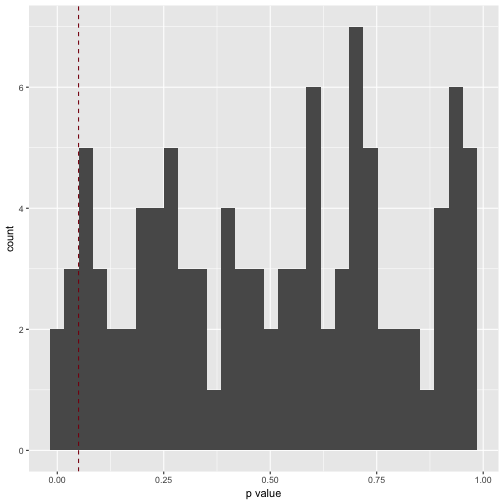

Correlation of means score with external criteria

OK, the correlation of the mean score with some external criteria surely is the central (first) idea to see how well the scale may have measured what it should measure.

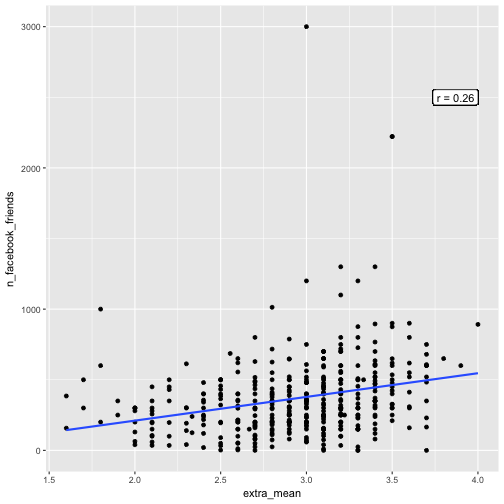

We could assume that there is an association of extraversion and the number of Facebook friends.

cor(x = e$extra_mean, y = e$n_facebook_friends, use = "complete.obs") -> cor_mean_FB

cor_mean_FB

## [1] 0.2558908

Hm, not really that much; however, in real life you have to be happy with non-perfect things…

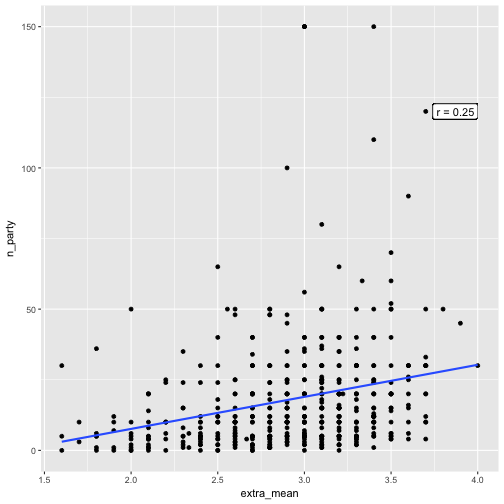

There are a number of similar behavioral indicators in the data set besides number of FB friends. Let’s look at each in turn.

e %>%

select(extra_mean, time_conversation, n_party, n_hangover) %>%

correlate %>%

focus(extra_mean) %>%

mutate_if(is.numeric, funs(round), digits = 2) -> corr_emean_criteria

htmlTable(corr_emean_criteria)

| rowname | extra_mean | |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | time_conversation | -0.11 |

| 2 | n_party | 0.25 |

| 3 | n_hangover | 0.11 |

Basically not much, maybe n_party can be of interest.

Let’s plot a scatterplot.

e %>%

select(extra_mean, n_facebook_friends) %>%

qplot(x = extra_mean, y = n_facebook_friends, data = .) +

geom_smooth(method = "lm", se = FALSE) +

geom_label(x = 4, y = 2500, label = paste("r = ", round(cor_mean_FB, 2), sep = ""), hjust = 1)

## Warning: Removed 90 rows containing non-finite values (stat_smooth).

## Warning: Removed 90 rows containing missing values (geom_point).

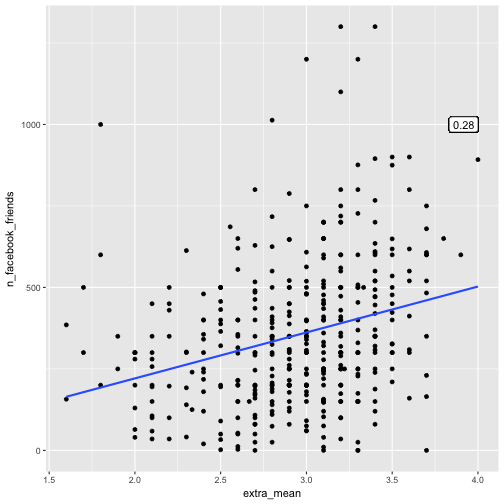

Let’s skip the extreme high values of FB friends. The correlation appeared to got stronger:

e %>%

select(extra_mean, n_facebook_friends) %>%

filter(n_facebook_friends < 1500) %>%

correlate %>%

focus(extra_mean) -> cor_mean_FB_filtered

cor_mean_FB_filtered

## # A tibble: 1 × 2

## rowname extra_mean

## <chr> <dbl>

## 1 n_facebook_friends 0.2774732

e %>%

select(extra_mean, n_facebook_friends) %>%

filter(n_facebook_friends < 1500) %>%

qplot(x = extra_mean, y = n_facebook_friends, data = .) +

geom_smooth(method = "lm", se = FALSE) +

geom_label(x = 4, y = 1000, label = round(cor_mean_FB_filtered$extra_mean[1], 2), hjust = 1)

And now a scatterplot of extra_mean and n_party.

e %>%

select(extra_mean, n_party) %>%

qplot(x = extra_mean, y = n_party, data = .) +

geom_smooth(method = "lm", se = FALSE) +

geom_label(x = 4, y = 120, label = paste("r = ", corr_emean_criteria$extra_mean[2], sep = ""), hjust = 1)

## Warning: Removed 18 rows containing non-finite values (stat_smooth).

## Warning: Removed 18 rows containing missing values (geom_point).

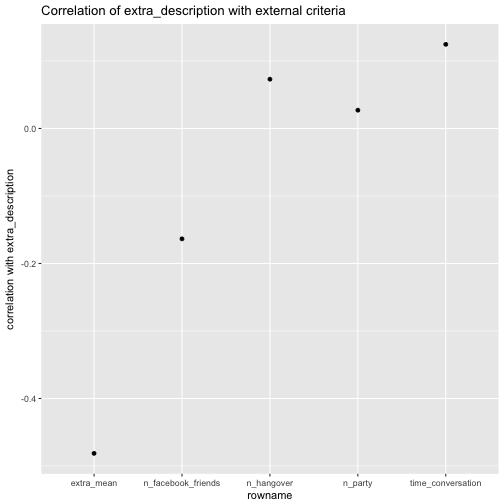

Correlation of extra_description with external criteria

Conventional psychometric knowledge holds that a psychometric ought to consist of several items. However, some renegades argue that “one-item wonder” can do an equally good job of predicting some external criteria. That’s no small claim, because if they do, there’s little to argue in favor of the longer, and thought more sophisticated methods in psychometry.

Of course, here we only play around a little, but let’s see what will happen:

extra_description: One item self-description of extroversionextra_vignette: One item vignette (self-description) of extraversion

We start with extra_description:

e %>%

select(extra_description, time_conversation, n_party, n_hangover, n_facebook_friends, extra_mean) %>%

correlate %>%

focus(extra_description) %>%

ggplot(aes(x = rowname, extra_description)) +

geom_point() +

ggtitle("Correlation of extra_description with external criteria") +

ylab("correlation with extra_description")

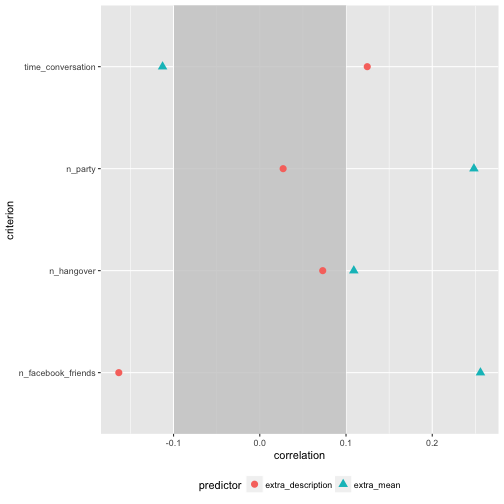

Let’s compare the correlation of extr_description with the external criteria to the correlation of extra_mean wit the external criteria.

e %>%

select(extra_description, time_conversation, n_party, n_hangover, n_facebook_friends) %>%

correlate %>%

focus(extra_description) %>%

mutate(predictor = "extra_description") %>%

rename(correlation = extra_description) -> corr_extra_description

e %>%

select(extra_mean, time_conversation, n_party, n_hangover, n_facebook_friends) %>%

correlate %>%

focus(extra_mean) %>%

mutate(predictor = "extra_mean") %>%

rename(correlation = extra_mean) -> corr_extra_mean

rbind(corr_extra_description, corr_extra_mean) -> corr_compare

corr_compare %>%

rename(criterion = rowname) -> corr_compare

Now let’s plot the difference in correlation strength for the two predictors of the external behavioral criteria.

corr_compare %>%

ggplot +

aes(x = criterion, y = correlation, color = predictor, fill = predictor) +

geom_rect(ymin = -0.1, ymax = 0.1, xmin = -10, xmax = 10, fill = "grey80", alpha = .2, color = NA) +

geom_point(aes(shape = predictor), size = 3) +

theme(legend.position = "bottom") +

coord_flip()

Of interest, the correlation of number of Facebook friends is quite different for extra_description compared with the correlation of extra_mean. For the rest, the difference is not “too” strong.

Assocation of extra_vignette with external criteria

extra_vignette needs some upfront preparation:

count(e, extra_vignette)

## # A tibble: 4 × 2

## extra_vignette n

## <fctr> <int>

## 1 119

## 2 keine Antwort 65

## 3 passt insgesamt 238

## 4 passt insgesamt nicht 79

recode(e$extra_vignette, "keine Antwort" = "no_answer", "passt insgesamt" = "fit", "passt insgesamt nicht" = "no_fit", .default = NA_character_) -> e$extra_vignette

count(e, extra_vignette)

## # A tibble: 4 × 2

## extra_vignette n

## <fctr> <int>

## 1 no_answer 65

## 2 fit 238

## 3 no_fit 79

## 4 NA 119

Let’s compute the mean value for each group of extra_vignette:

e %>%

select(extra_vignette, extra_description, time_conversation, n_party, n_hangover, n_facebook_friends, extra_mean) %>%

filter(extra_vignette %in% c("fit", "no_fit")) %>%

group_by(extra_vignette) %>%

summarise_all(funs(mean), na.rm = TRUE) %>%

mutate_if(is.numeric, funs(round), digits = 1) -> comp_extra_vignette

comp_extra_vignette %>%

htmlTable

| extra_vignette | extra_description | time_conversation | n_party | n_hangover | n_facebook_friends | extra_mean | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | fit | 2.7 | 12.1 | 20.7 | 11.2 | 417 | 3 |

| 2 | no_fit | 4 | 23.7 | 13.5 | 6.7 | 274.7 | 2.6 |

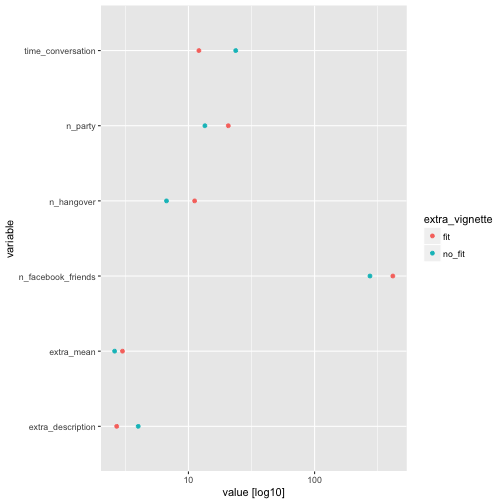

Let’s plot that too.

comp_extra_vignette %>%

gather(key = variable, value = value, -extra_vignette) %>%

ggplot +

aes(x = variable, y = value, color = extra_vignette, fill = extra_vignette) +

geom_point() +

scale_y_log10() +

coord_flip() +

labs(y = "value [log10]")

We see that the fit dot is sometimes at a higher value (to the right) compared to the no_fit dot, which matches expectations. But this is, as can be seen, not always the case. Of interest, extra_mean shows small differences only.

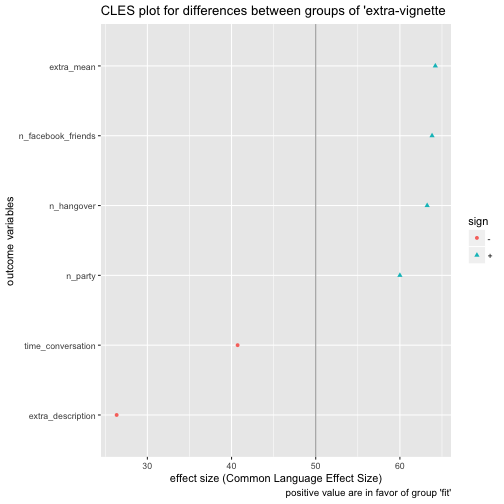

OK, but what’s a big difference? Let’s compute the CLES measure of effect size for each criterion (here column of the table above) with extra_vignette as grouping variable.

First we prepare the data:

library(compute.es)

dplyr::count(e, extra_vignette)

e %>%

select(time_conversation, n_party, n_hangover, n_facebook_friends, extra_mean, extra_description, extra_vignette) %>%

filter(extra_vignette %in% c("fit", "no_fit")) %>%

na.omit() -> e3

e3 %>%

select(-extra_vignette) %>%

map(~t.test(. ~ e3$extra_vignette)) %>%

map(~compute.es::tes(.$statistic,

n.1 = nrow(dplyr::filter(e, extra_vignette == "fit")),

n.2 = nrow(dplyr::filter(e, extra_vignette == "no_fit")))) %>%

map(~do.call(rbind, .)) %>%

as.data.frame %>%

t %>%

data.frame %>%

rownames_to_column %>%

rename(outcomes = rowname) ->

extra_effsize

Then we plot ‘em.

extra_effsize %>%

dplyr::select(outcomes, cl.d) %>%

mutate(sign = ifelse(cl.d > 50, "+", "-")) %>%

ggplot(aes(x = reorder(outcomes, cl.d), y = cl.d, color = sign)) +

geom_hline(yintercept = 50, alpha = .4) +

geom_point(aes(shape = sign)) +

coord_flip() +

ylab("effect size (Common Language Effect Size)") +

xlab("outcome variables") +

labs(title = "CLES plot for differences between groups of 'extra-vignette",

caption = "positive value are in favor of group 'fit'") -> CLES_plot

CLES_plot

Pooh, quite some fuzz. See this post for some explanation on what we have just done.

Now, what do we see? extra_description went plain wrong; extra_mean captures some information. We should note that some overcertainty may creep in here (and elsewhere). Our estimates are based on sample, not population values. So it is doubtful whether we can infer that futures samples (all we are interested in) will behave as predicted (here).

Reliability

The only type of reliability we can compute is internal consistency, for we have no second measurement. It should be stressed that even if high reliability is given we do not know whether the measurement measured what we hope for. If reliability is not high, then we do know that our measurement failed. So reliability can be seen as necessary, but not sufficient, for gaining confidence in an instrument. That’s why validity (often read as correlation) is more telling: If association is there, we probably know what we wanted to know. Our measurement device as expected.

e %>%

select(i01:i10) %>%

psych::alpha()

##

## Reliability analysis

## Call: psych::alpha(x = .)

##

## raw_alpha std.alpha G6(smc) average_r S/N ase mean sd

## 0.78 0.79 0.81 0.28 3.9 0.015 2.9 0.46

##

## lower alpha upper 95% confidence boundaries

## 0.75 0.78 0.81

##

## Reliability if an item is dropped:

## raw_alpha std.alpha G6(smc) average_r S/N alpha se

## i01 0.75 0.76 0.77 0.26 3.2 0.017

## i02r 0.76 0.77 0.78 0.27 3.4 0.016

## i03 0.81 0.81 0.82 0.33 4.4 0.013

## i04 0.75 0.76 0.77 0.26 3.2 0.017

## i05 0.75 0.76 0.77 0.26 3.2 0.017

## i06r 0.76 0.77 0.78 0.27 3.4 0.016

## i07 0.76 0.77 0.79 0.27 3.4 0.016

## i08 0.76 0.78 0.79 0.28 3.5 0.016

## i09 0.77 0.78 0.79 0.28 3.6 0.016

## i10 0.78 0.79 0.80 0.30 3.8 0.015

##

## Item statistics

## n raw.r std.r r.cor r.drop mean sd

## i01 499 0.69 0.71 0.68 0.60 3.3 0.68

## i02r 498 0.63 0.63 0.59 0.50 3.1 0.80

## i03 500 0.33 0.30 0.16 0.14 1.9 0.92

## i04 498 0.68 0.69 0.67 0.57 3.2 0.73

## i05 498 0.69 0.70 0.68 0.59 3.1 0.77

## i06r 499 0.62 0.62 0.57 0.50 2.9 0.77

## i07 498 0.62 0.62 0.57 0.50 3.0 0.73

## i08 499 0.61 0.60 0.53 0.47 2.9 0.86

## i09 499 0.55 0.57 0.49 0.43 3.4 0.71

## i10 498 0.51 0.49 0.39 0.34 2.2 0.90

##

## Non missing response frequency for each item

## 1 2 3 4 miss

## i01 0.01 0.08 0.46 0.45 0.00

## i02r 0.04 0.16 0.45 0.35 0.01

## i03 0.41 0.33 0.19 0.06 0.00

## i04 0.01 0.16 0.43 0.41 0.01

## i05 0.02 0.20 0.47 0.30 0.01

## i06r 0.05 0.18 0.54 0.22 0.00

## i07 0.02 0.21 0.54 0.23 0.01

## i08 0.06 0.23 0.44 0.27 0.00

## i09 0.01 0.10 0.41 0.47 0.00

## i10 0.21 0.43 0.26 0.10 0.01

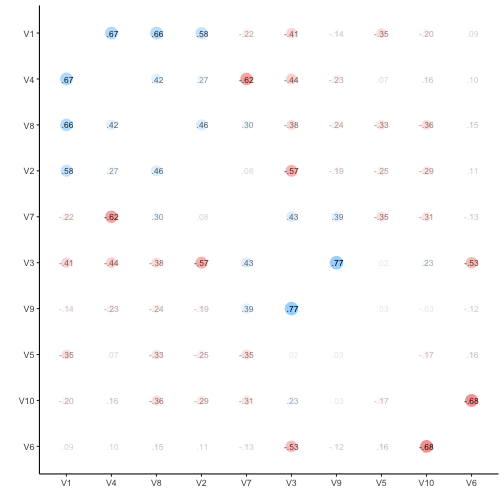

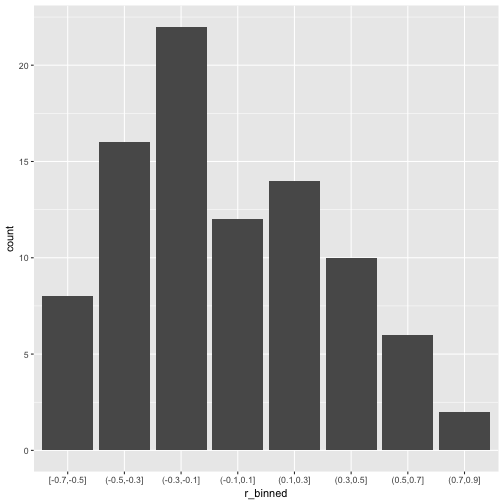

Internal consistency, as an intuition, can be understood as something like the mean item inter correlation (the numbers are different, but the idea is similar). Note that Alpha is also a function of the number of items (the higher the number of items, the larger Alpha will be, not a nice property). And, even if Alpha is high that is no sufficient evidence that the data is unidimensional.

With the help of the manual of psych let’s dissect the output:

raw_alpha: That’s the typical alpha you might expect (based on the covariances)average_r: Mean inter-item correlationS/N: signal-noise-ration (see manual for details)- se: standard error (precision of estimation in Frequentist theory)

rar.r: “The correlation of each item with the total score, not corrected for item overlap.”std.r: “The correlation of each item with the total score (not corrected for item overlap) if the items were all standardized”r.cor: “Item whole correlation corrected for item overlap and scale reliability”r.drop: “Item whole correlation for this item against the scale without this item”

Here’s some input on how to work with this function.

In sum, we may conclude that the internal consistency is good; item i03 appearing somewhat problematic as internal consistency would be higher without that guy.

Remember that i03 had the lowest mean? Fits together.

Validity, next step

Let’s go back to some “validity” concerns, as this step is more important than reliability.

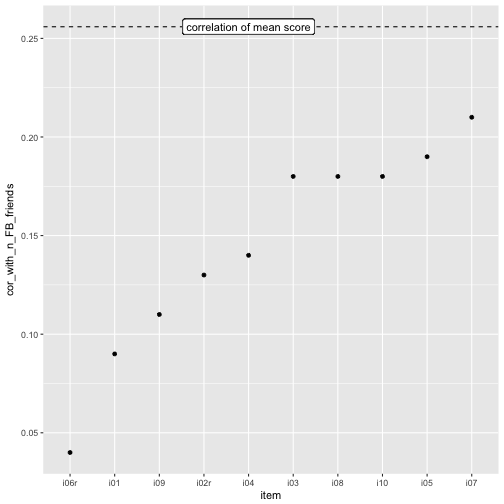

Single-item external validity

Let’s compute the correlation of each item with a given external criterion. If the correlation of a single item is not worse than the total score, ~we~ the item score, that is the instrument is in trouble.

e %>%

select(i01:i10, n_facebook_friends) %>%

correlate %>%

focus(n_facebook_friends) %>%

mutate_if(is.numeric, round, digits = 2) %>%

rename(item = rowname, cor_with_n_FB_friends = n_facebook_friends) %>%

ggplot +

aes(x = reorder(item, cor_with_n_FB_friends), y = cor_with_n_FB_friends) +

geom_point() +

xlab("item") +

geom_hline(yintercept = cor_mean_FB, linetype = "dashed") +

geom_label(x = 5, y = cor_mean_FB, label = "correlation of mean score")

OK, the mean score is “somewhat” better than the most predictive item, i07, but really really not much.

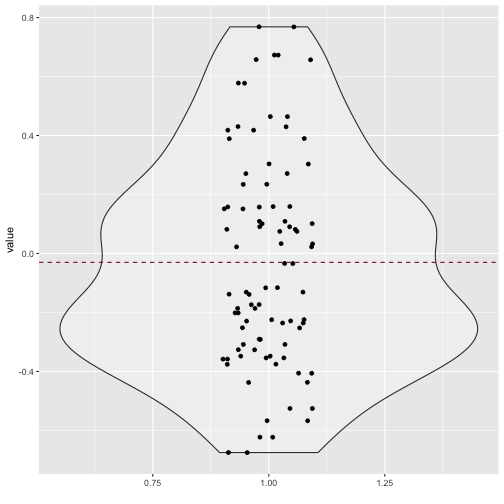

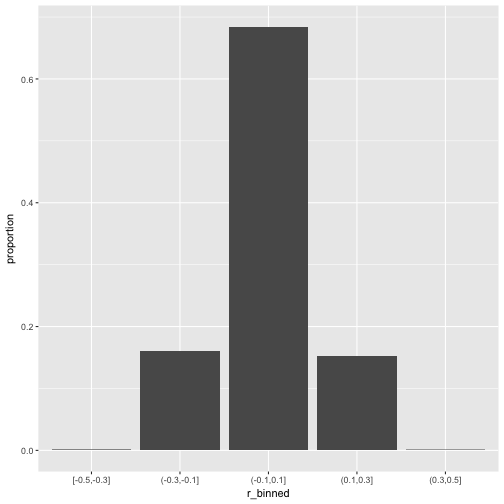

Dichotomization

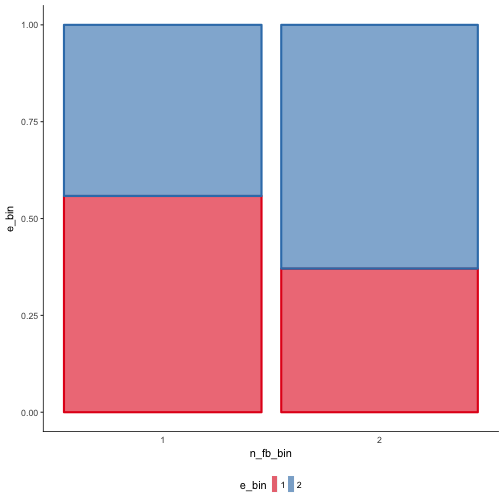

I know, some will say “don’t to that, my Goodness! Power!”, yes that’s true, but hey, let’s loose some power! After all, we are being more conservative, in a way. What do we get for this price? A quite tangible explanation. More precisely, let’s median split extra_mean and n_facebook_friends.

e %>%

select(extra_mean, n_facebook_friends) %>%

mutate(e_bin = ntile(extra_mean, 2),

n_fb_bin = ntile(n_facebook_friends, 2)) %>%

na.omit %>%

plotluck(e_bin ~ n_fb_bin)

Hm, at least some association seem to be present.

Non-linear association of extraversion with FB friends

We could apply different model, not only the linear model (ie., correlation) to discern possible patterns between the variables. This is an interesting field, but not my goal for today. Let’s dive here some other day; some time ago we have used some “machine learning” methods for this purpose in this paper.

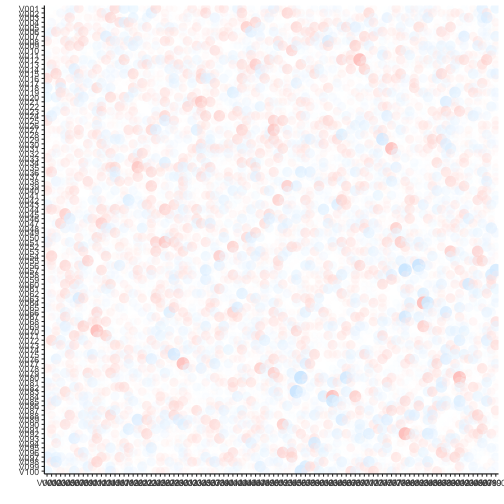

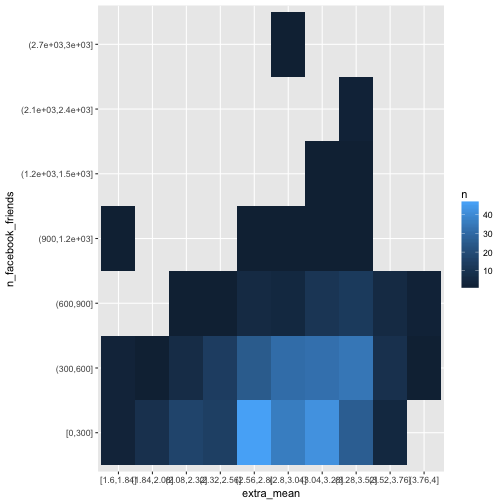

Finer categorial analysis

The idea of the dichotomization can be put to level of finer granularity. Why 2 buckets (bins)? Why not some more? This would give us a more precise picture. Additionally, it may argued that no measurement device exist with infinite granularity – which is posited by continuous variables (see Brigg’s book on that).

Of course, many ways exist to bin a metric variable into some discrete buckets including Sturges’ rule, or Freedman’s rule (see here for some explanation). But let’s go easy, and pick - arbitrarily - ten buckets for each variable of equal width (not of equal n).

e %>%

select(extra_mean, n_facebook_friends) %>%

na.omit %>%

mutate_all(cut_interval, n = 10) %>%

count(extra_mean, n_facebook_friends) %>%

ggplot(aes(x = extra_mean, y = n_facebook_friends, fill = n)) +

geom_bin2d()

One problem with this method here is that empty buckets are silently dropped which renders the procedure fruitless for our purpose.

Let’s try differently, and let’s kick out extreme values.

e %>%

select(extra_mean, n_facebook_friends) %>%

na.omit %>%

filter(n_facebook_friends < 1500) %>%

mutate_all(ntile, n = 10) %>%

count(extra_mean, n_facebook_friends) %>%

ggplot(aes(x = factor(extra_mean), y = factor(n_facebook_friends), fill = n)) +

geom_bin2d(aes(fill = n))

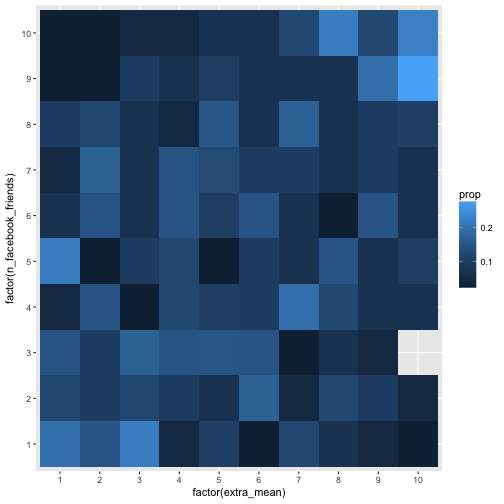

Ah, that’s way better. Well, we do not see much, but the (absolute) numbers are not equal among the buckets.

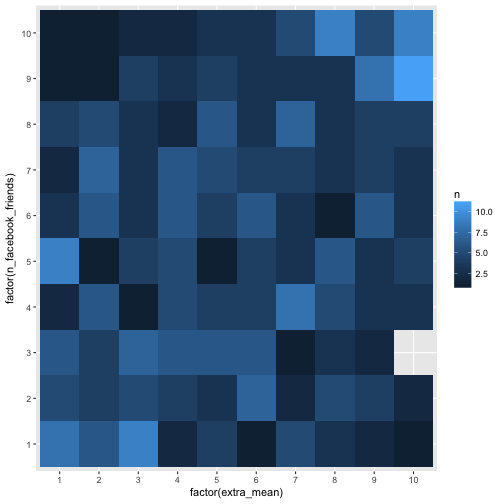

But even better would be if we could devise the probability of \(y_n\) given \(x_n\). More verbose, if the probability to have a 1 in X given Y is, say, 5 equals the probability $$p(X=2 |

Y=5)$$, then we will say that these two events are not related, or, more precisely, independent. |

Let’s try it this way:

e %>%

select(extra_mean, n_facebook_friends) %>%

na.omit %>%

filter(n_facebook_friends < 1500) %>%

mutate_all(ntile, n = 10) %>%

count(n_facebook_friends, extra_mean) %>%

group_by(n_facebook_friends) %>%

mutate(prop = n/sum(n)) %>%

ggplot(aes(x = factor(extra_mean), y = factor(n_facebook_friends), fill = prop)) +

geom_bin2d(aes(fill = prop))

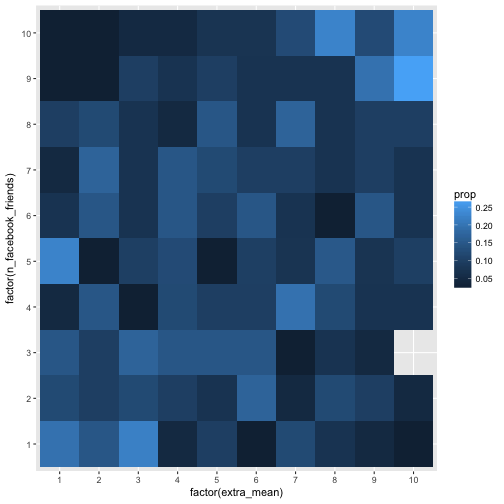

Here we summed up rowwise. Let’s compare to what happens if we sum up colwise.

e %>%

select(extra_mean, n_facebook_friends) %>%

na.omit %>%

filter(n_facebook_friends < 1500) %>%

mutate_all(ntile, n = 10) %>%

count(extra_mean, n_facebook_friends) %>%

group_by(extra_mean) %>%

mutate(prop = n/sum(n)) %>%

ggplot(aes(x = factor(extra_mean), y = factor(n_facebook_friends), fill = prop)) +

geom_bin2d(aes(fill = prop))

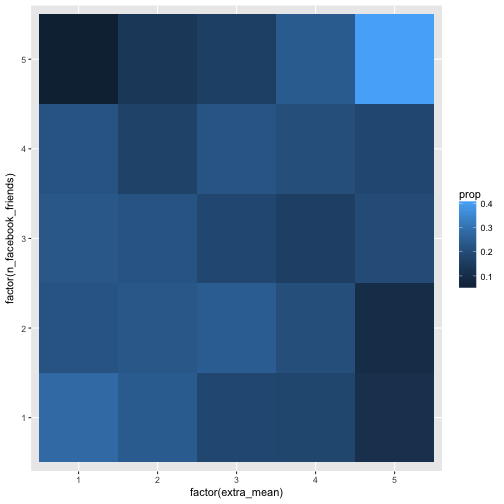

Hm, maybe the association is too weak to see in that many buckets. Let’s reduce the bucket number by factor 2 (5 buckets), and check the picture again.

e %>%

select(extra_mean, n_facebook_friends) %>%

na.omit %>%

filter(n_facebook_friends < 1500) %>%

mutate_all(ntile, n = 5) %>%

count(extra_mean, n_facebook_friends) %>%

group_by(extra_mean) %>%

mutate(prop = n/sum(n)) %>%

ggplot(aes(x = factor(extra_mean), y = factor(n_facebook_friends), fill = prop)) +

geom_bin2d(aes(fill = prop))

| This level of granularity seems more in place. Some association can be eyeballed. The conditional probabilities (p(Y=y | X=x)) are not equal, thus, we can say, some dependencies exist. Note that this analyses is in a way more concrete than the correlation. Why? For two reasons. First, we speak on real observations, not on abstract parameters such as \(r\) (see James Grice’ idea on Observation Oriented Modeling). Second, we do not shrunk down the information to one number only, but too much more (here 25=5x5), this amount of information can easily be recognized by the eye. |

There is a wealth on categorial data analysis tools available, notable Agresti’s work. Thus, much more could be said and done.

CLES

The “Common language effect size” (CLES) is an interesting approach to put effect sizes, such as $r$, to a more tangible language. Basically, CLES tells us, if we were to draw two observations, one of each of two group (here: high vs. low extraversion), what’s the probability that the observation from the “experimental” group (or reference group, more generally) will show higher value in the outcome variable? Note that it is note the same as a Bayesian predictive distribution.

An R function for that purpose exists, but see this great post for more in depth info.

Final thoughts

The central idea of this post was to see whether the mean score is more predictive to some criterion than single items. I argue that validity is more important than reliability, albeit reliability (Cronbach’s Alpha) is typically reported in (applied) papers, but validity to a lesser degree.

Second, we explored (a bit) the notion whether the association is better captured in several numbers, and not only in one, as is done by the correlation value. This idea is based on the definition of independence in probability theory.

We did not dive here in factor analytic waters, nor did we discussed Item Response Theory, amongst other ideas left out. These ideas are worthwhile certainly, but beyond the primary aims of this post.

Related work

There’s a lot on scale validation on the internet; see here for an example. For skepticism on psychometric scale, and for advocates of single item scales, see here, or here, and here for a broader discussion.

SessionInfo

sessionInfo()

## R version 3.3.2 (2016-10-31)

## Platform: x86_64-apple-darwin13.4.0 (64-bit)

## Running under: macOS Sierra 10.12.1

##

## locale:

## [1] en_US.UTF-8/en_US.UTF-8/en_US.UTF-8/C/en_US.UTF-8/en_US.UTF-8

##

## attached base packages:

## [1] stats graphics grDevices utils datasets methods base

##

## other attached packages:

## [1] compute.es_0.2-4 plotluck_1.1.0 psych_1.6.9 corrr_0.2.1

## [5] htmlTable_1.7 dplyr_0.5.0 purrr_0.2.2.9000 readr_1.0.0

## [9] tidyr_0.6.0 tibble_1.2 ggplot2_2.2.0 tidyverse_1.0.0

## [13] knitr_1.15

##

## loaded via a namespace (and not attached):

## [1] Rcpp_0.12.7 magrittr_1.5 mnormt_1.5-5

## [4] munsell_0.4.3 colorspace_1.3-0 R6_2.2.0

## [7] highr_0.6 stringr_1.1.0 plyr_1.8.4

## [10] tools_3.3.2 parallel_3.3.2 grid_3.3.2

## [13] gtable_0.2.0 DBI_0.5-1 htmltools_0.3.5

## [16] yaml_2.1.14 lazyeval_0.2.0.9000 rprojroot_1.1

## [19] digest_0.6.10 assertthat_0.1 RColorBrewer_1.1-2

## [22] evaluate_0.10 rmarkdown_1.1.9016 labeling_0.3

## [25] stringi_1.1.2 scales_0.4.1 backports_1.0.4

## [28] foreign_0.8-67