Below some consideration on what to read in summer times. In German language.

Lesezeit/reading time: 10-15 Min.

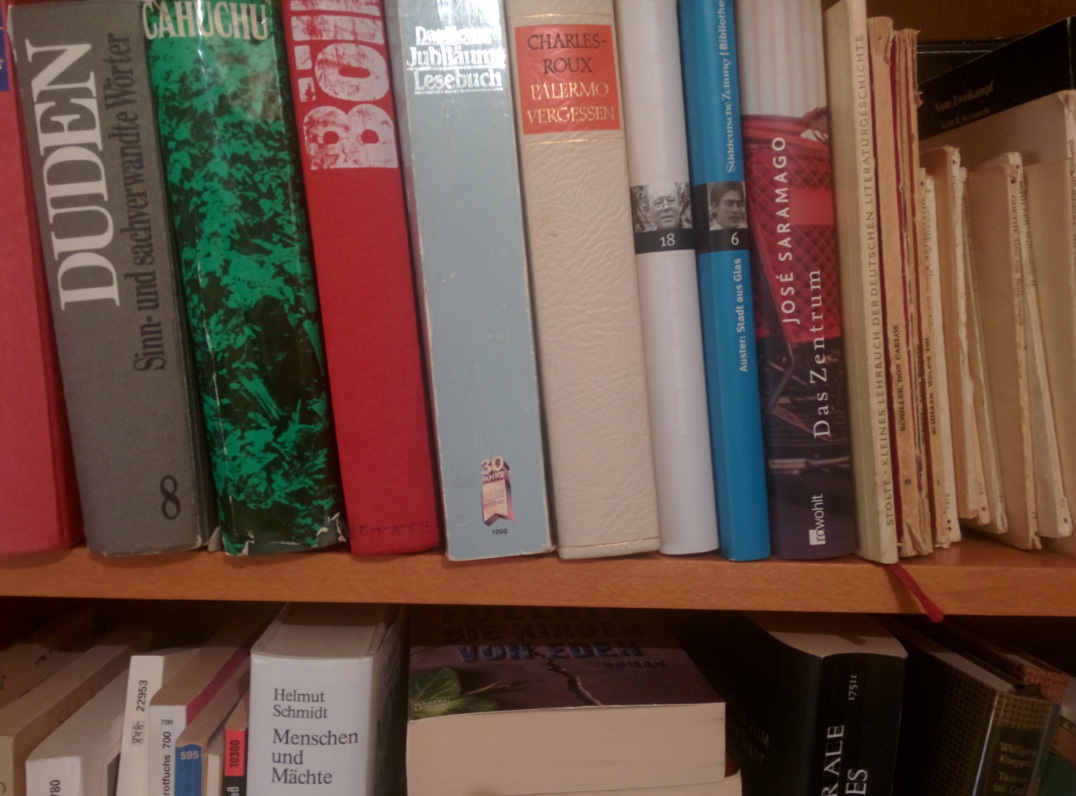

Literaturempfehlung Sommer 2016

Was soll ich lesen?

Sommer, Sonne, Sonnenschein — ab in den Süden. Die Zeile “Lesen, lesen, lesen, lesen” würde sich nach meinem Dafürhalten auch ganz gut in den Song einpassen. Dafür hier ein paar Literaturempfehlungen. Von einer anständigen Sommerlektüre erwarte ich zweierlei: Dass die Kunst unterhaltsam sei. Zweitens, wenn als der Dampf sich nach dem Lesen erhebt, dass etwas zurückbleibt, außer dem Dampf. Beides gleichzeitig zu finden ist gar nicht so leicht.

Vielleicht denkt man das zu jeder Zeit, aber gerade aktuell die Welt besonders in Unruhe. Schlimme oder zumindest besorgende Nachrichten häufen sich; Tumult wohin man blickt. Da scheinen Anregungen zu Themen wie

Praktische Ethik, Grenzen, Grenzen der Ethik (Stichwort Flüchtlinge oder besser die Katastrophen, die Menschen zwingen zu fliehen) Demokratie, die offene Gesellschaft, ihr Ursprung und ihre Feinde Das Böse, sein Psychogramm und sein Phänomenologie am Fallbeispiel dem Zeitgeschehen auf den Nabel zu schauen. Manchmal frage ich mich, ob man in Anbetracht der Probleme der heutigen Zeit noch in Ruhe Grundlagenforschung betreiben darf (was ich tue). Jedenfalls heute und diesen Sommer keine Empfehlungen (auch deswegen) zur Grundlagenforschung, sondern drei Literaturempfehlungen zur Psycho-Philosophie des aktuellen Zeitgeschehens.

Empfehlung 1: Praktische Ethik von Peter Singer

Zugeben: kein Geheimtipp und schon gar nicht neu. Außerdem gibt es von demselben Autor aktuelle, ganz neue Werke, wie zB. effektiver Altruismus, in welchem der Autor seine Gedanken konsequent und mit praktischer Perspektive fortführt. Sein “Hauptwerk”, die Praktische Ethik ist und bleibt aber (für mich) eines der Bücher, die mich am meisten zum Nachdenken angeregt haben und meine Meinung zu vielen Themen der praktischen Ethik am stärksten beeinflusst haben, weitergebracht haben.

Peter Singer ist ein kontrovers diskutierter Philosoph; er wurde sogar vielfach angefeindet für seine Äußerungen (zB., dass hoch entwickelte Tiere schätzenswerter sind als Babies weil empfindungsfähiger). Wahrscheinlich ist er (trotzdem oder gerade deshalb) der bekannteste zeitgenössische Denker zur praktischen Ethik. Entscheidend ist auch nicht, ob und wie viele seine Thesen man selber unterstützt; seine Argumentationslinie ist einfach lehrreich. Seine Gedankenkette besticht durch Einfachheit, Klarheit und Stringenz. Brilliant! Ein großer Geist; Freude beim Lesen über soviel geistige Klarheit! Und: In Erinnerung geblieben ist mir auch folgender Satz von ihm. Und zwar wurde er bei einem Vortrag in — war es Deutschland oder Österreich? — so laut ausgepfiffen, dass er seinen Vortrag abbrechen musste. In dem Zusammenhang erwähnte er dieses Zitat (in etwa so): “Ihre Meinung mag von meiner diametral abweichen, aber ich werde bis zum Schluss Ihr Recht verteidigen, dass Sie reden dürfen”.

In der Praktischen Ethik diskutiert er auch Fragen im Zusammenhang mit Flüchtlingen; auch ein interessantes Gedankenexperiment ist in dem Kapitel enthalten. Das Buch ist dünn und klein; Reklam. Zumindest lässt das die Ausrede vom Gepäckaufstau nicht gelten:-)

Empfehlung 2: Die offene Gesellschaft von Karl Popper

OK, auch ein alter Herr des 20. Jahrhunderts. Aber einer, der es in sich hat. Ein Halb-Österreicher (ähnlich wie Singer, dessen Eltern vor den Nazis aus Österreich geflohen sind in die angelsächsische Welt nach Australien), da er wegen der Nazis nach Neuseeland und dann England ausgewandert ist. Ähnlich wie Singer benutzt er einfache Worte, um klare und tiefe Gedanken auszudrücken. Genuss!

Seine Hauptthese kann man wohl so zusammenfassen: Die Offene Gesellschaft ist die Überwindung der “Urhorde” — der archaischen Gesellschaft und ihre Weiterführung in Staatsformen wie Stammesgesellschaft, Monarchie und totalitären Regimen. Auch der Nationalstaat — die Nation ist wenig mehr als eine modernere Version der Horde — müsse letztlich überwunden werden. Totalitäres Gedankentum findet sich nicht erst in Hitler-Deutschland; vielmehr identifiziert er mit Platon der ersten mächtigen geistigen Vater der totalitären, nicht-offenen Gesellschaft aus. Aristoteles kommt da auch nicht gut weg; aber als neuzeitlicher Hansdampf der Verführer, Dünnbrettbohrer und schaumschlagende Laberbacke wird vor allem Hegel (und Fichte) gebrandmarkt. Marx wird zwar komplett für “falsizifiert” (ein Term von Popper) erklärt, aber vergleichsweise respektabel abgehandelt. Neben Marx ist Popper wohl (einer) der einflussreichste Denker des 20. Jahrhunderts. Sein Buch ist Bildung im besten Sinne; seine Theorie der freien Gesellschaft (vs. Horde bzw. geschlossen-totalitäre Gesellschaft) faszinierend im psychologisch-soziologischem Sinne. Gut, es ist einiges zu lesen (2 Bände, recht beleibt), aber ein Buch, dass für mich prägend im Denken war und ist. Lesen!

Empfehlung 3: Männerphantasien von Klaus Theweleit

Mit einem Buch dieses Titels könnte man in der Ubahn einige Blick ernten, deren Urheber eine andere Lektür vermute. Diesem Anspruch kommt das Buch nicht nach. Die Männerphantasien, die Klaus Theweleit hier analysiert, haben kaum, nichts! mit Erotik zu tun. Im Gegenteil, wahrscheinlich: Er beschreibt die Psyche des nationalsozialistischen Soldaten, die “aggresionsgesättigt” und nicht voll ich-ausgebildet ist, trotzem aber hochfunktional. Gekennzeichnet von Kühle, Beziehungsunfähigkeit, Gefühlskälte, Aggressivitätswalle, Heldenphantasien. Zwar bedient er sich stark einer tiefenpsychologisch-psychoanalytischen Denkschule, aber vor allem besticht (mich) seine Beobachtungs- und Interpretationsfähigkeit. Auf einer einzigen Leseseite findet sich mehr Reichhaltigkeit an gewagten Hypothesen (im besten Sinne) als in dem meisten an modern-wissenschaftlichem Papier, was in “hochgerankten” Fachzeitschriften publiziert ist. Das Psychogramm der Tötungslust oder die Lust am Bösen, könnte man sagen, führt er auf ein patriarchalisches Eltern- besser: Vaterhaus zurück. Eine umfassende (>1000 Seiten…) Analyse der Psyche von “richtig bösen” Menschen, wie Rudolph Höss, der auch besprochen wird neben einer ganzen Reihe weiterer Nazi-Größen. Ob das alles stimmt, was er schreibt? Weiß ich nicht; ich weiß nicht einmal, ob es darauf ankommt. Ob es übertragbar ist auf heute? Nicht sicher. Aber es ist lehrreich, fesselnd, originell, gewagt. Eine Aufarbeitung mit der Psychologie des Bösen in (unserer eigenen) deutschen Vergangenheit — tiefsichtiger als moderne Bücher wie die von Psychologen wie Baumeister oder Zimbardo oder (schon tiefgehender) Welzer. Keine leichte Kost, aber man kann viel Lernen über Bilder der bösen Psyche und ihre (Ab-) Gründe.

Was soll ich lesen?

Eine große Frage! Tja. Viel Spaß am Strand!