It may seem bewildering that the standard deviation (sd) of a vector X is (generally) unequal to the mean absolute deviation from the mean (MAD) of X, ie.

\(sd(X) \ne MAD(X)\).

One could now argue this way: well, sd(X) involves computing the mean of the squared \(x_i\), then taking the square root of this mean, thereby “coming back” to the initial size or dimension of x (i.e, first squaring, then taking the square root). And, MAD(X) is nothing else then the mean deviation from the mean. So both quantities are very similar, right? So one could expect that both statistics yield the same number, given they operate on the same input vector X.

However, this reasoning if flawed. As a matter of fact, sd(X) will almost certainly differ from MAD(X).

This post tries to give some intuitive understanding to this matter.

Well, we could of course lay back and state that why for heaven’s sake should the two formulas (sd and MAD) yield the same number? Different computations are involved, so different numbers should pop out. This would cast the burden of proof to the opposite party (showing that there are no differences). However, this answer does not really appeal if one tries to understand why it things are the way they are. So let’s try to develop some sense out of it.

Looking at the formulas

The formula above can be written out as

\[\sqrt{\frac{1}{n} \sum{x^2_i}} \ne \frac{1}{n} \sum{x_i}\]where \(X\) is a vector of some numeric values. For the sake of simplicity \(x_i\) refers to the difference of some value to its mean.

Looking at the formula above, our question may be more poignantly formulated as “why does the left hand side where we first square and then take the opposite operation, square root, does not yield the same number as the right hand side?”. Or similarly, why does the square root not “neutralize” or “un-do” the squaring?

If we suspect that the squaring-square-rooting is the culprit, let’s simplify the last equation a bit, and kick-out the \(\frac{1}{n}\) part. But note that we are in fact changing the equation here.

For generality, let’s drop the notion that \(x_i\) necessarily stands for the difference of some value of a vector to the mean of the vector. We just say now that \(x_i\) is some numeric value whatsoever (but positive and real, to make life easier).

Then we have:

\[\sqrt{ \sum{x^2_i}} \ne \sum{x_i}\]This equation is much nicer in the sense it shows the problem clearer. It is instructive to now square both sides:

\[\sum{x^2_i} \ne (\sum{x_i})^2\]In words, our problem is now “Why is the sum of squares different to the square of the sum?”. This problem may sound familiar and can be found in a number of application (eg., some transformation of the variance).

Let’s further simplify (but without breaking rules at this point), and limit our reasoning to a vector X of two values only, a and b:

\[a^2 + b^2 \ne (a+b)^2\]Oh, even more familiar. We clearly see a binomial expression here. And clearly:

\[a^2 + b^2 \ne (a+b)^2 = a^2 + 2ab + b^2\]Visualization

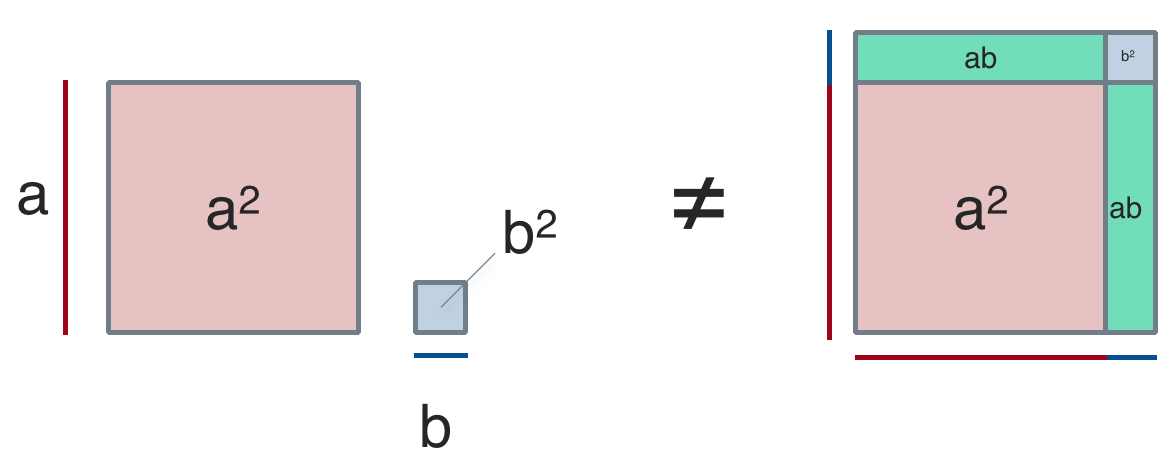

A helpful visualization is this:

.

.

This scheme makes clear that the difference between the left hand side and the right hand side are the two green marked areas. Both are \(ab\), so \(2ab\) in total. \(2ab\) is the difference between the two sides of the equation.

Going back to the average (1/n)

Remember that above, we deliberately changed the initial equation (the initial problem). That is, we changed the equation in a non-admissible way in order to render the problem more comprehensible and more focused. Some may argue that we should come back to the initial problem, where not sums but averages are to be computed. This yields a similar, but slightly more complicated reasoning.

Let us again stick to a vector X with two values (a and b) only. Then, the initial equation becomes:

\[\sqrt{ \frac{a^2}{2} + \frac{b^2}{2}} \ne \frac{a}{2} + \frac{b}{2}\]Squaring both sides yields

\[\frac{a^2}{2} + \frac{b^2}{2} \ne (\frac{a}{2} + \frac{b}{2})^2\]This can be simplified (factorized) as

\(\frac{1}{2} (a^2 + b^2) \ne \frac{1}{2^2}(a^2 + 2ab + b^2)\).

Now we have again a similar situation as above. The difference being that on the left hand side (1/2) if factored out; on the right hand side (1/4) is factored out. As the formulas are different (and similar to our reasoning above), we could stop and argue that is unlikely that both sides yield the same value.

Visualization 2

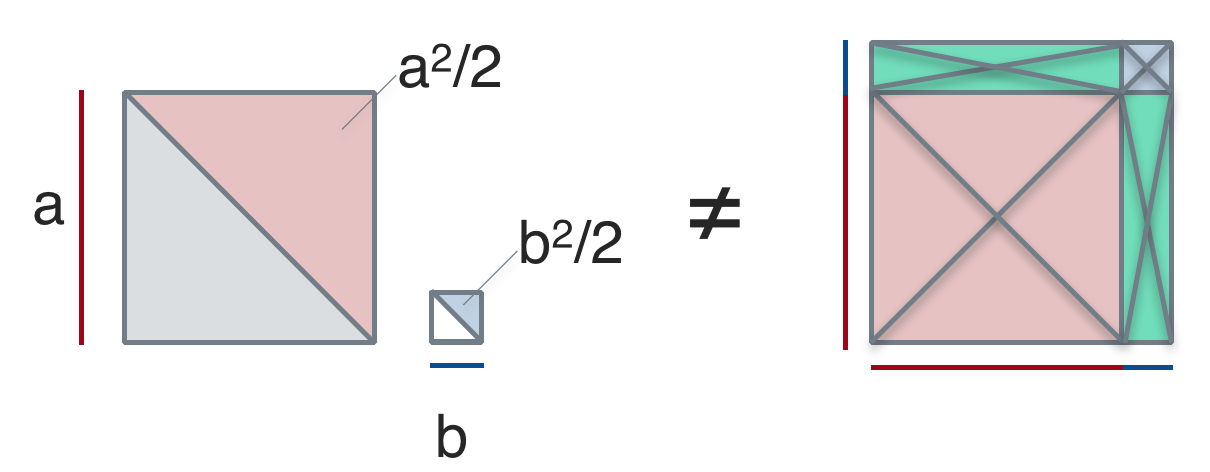

As a final step, let’s visualize the thoughts of the previous lines.

What this amazing forest of crossing lines wants to tell you is the following. For the left hand side, the diagonal lines divide \(a^2\) and \(b^2\) in two parts of equal size, i.e., \(a^2/2\) and \(b^2/2\).

For the right hand side, a similar idea applies. But the double-crossed (“x-type”) lines indicate that each of the four forms is divided in 4 equal parts, ie., \(a^2/4\), \(b^2/4\) and two times \(ab/4\).

From this sketch, again it appears unlikely that both sides would yield the same number. We have not proven that is impossible, but our reasoning suggests that it would be highly unlikely to see the same number on both sides of the equation.